- Home

- Gillian McDunn

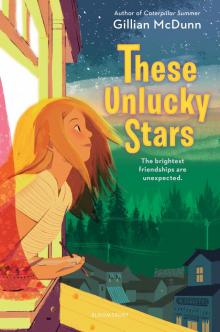

These Unlucky Stars Page 3

These Unlucky Stars Read online

Page 3

Today feels different. Ms. Palumbo’s words echo in my ears. These are Ray’s friends—not mine.

Thwack. Thwack. Thwack.

Sure, they say “hey, Annie” when I show up. But the truth is, they never ask me to play. I’m a girl and I’m younger than they are. They let me tag along. They’re friendly but not really my friends.

Ray’s best friend, Grant, aims from the three-point line. When he lets go, it soars in a long arc before going through the hoop. His light skin is flushed red underneath his sweaty blond hair. Grant grins quietly, but redheaded Tyler races around the court like he was the one who made the basket. He waves his arms wildly. “Nothing but net! Nothing but net!”

Someone moves beside me—it’s Faith, sitting on top of the picnic table. She used to be in Ray’s grade at Oak Branch, but two years ago her family moved to Mountain Ring. For some reason, she’s been hanging around the park every afternoon this week. Except for saying hi once or twice, we haven’t talked. Friendly but not friends.

What did Ms. Palumbo say? Take the initiative and start a conversation.

She sits cross-legged. Her hair is in lots of skinny braids and she has medium-brown skin. She’s wearing a green shirt.

Talking with Mr. Melendez and Ms. Palumbo was beyond weird, but maybe they had a little bit of a point about one thing. Maybe I do need a friend—one who’s just for me.

She uncaps a bottle of turquoise fingernail polish. Each nail she paints the same way: first a stripe of color down the middle, then a little flick of the brush that pushes the polish to the edges. She stays inside the lines the whole time.

I’m tired of watching and waiting. I don’t want to be stuck like a turtle in the road.

“Hey,” I say before I lose my nerve.

Faith looks up. “Hey.”

I clear my throat, not sure what to say next. “Is your family moving back to Oak Branch or something?”

She gets a look on her face that reminds me of shutters closing over a window. “No,” she says flatly. “I’m staying with my aunt Louise for a while.”

Okay, that did not go well. I should have known it wouldn’t be as easy as saying hi. Thanks a lot, Ms. Palumbo.

We’re quiet for a moment, watching the boys. Grant keeps looking over here and smiling. I don’t think it’s at me.

Faith blows on her fingers to dry them. Then she holds them in front of her. They sparkle in the sun.

“Tahitian Breeze,” she says.

She talked to me! I can’t mess this up.

I nod. “Well, it’s a great color. Just … really … great. I like it.”

Awkward. I’m about to go back to my sketchbook when she catches my eye. “Want me to do yours?”

I glance down at my nails, which are raggedy and have a little dirt under them. I wish I could blame that on this morning’s mud puddle, but I can’t. They usually look like this.

“Okay,” I say, wiping my hands on my pants.

She motions for me to sit on the picnic table, too, so I climb up next to her. She grabs my hand and peers at it carefully. Working steadily, she moves from one finger to the next, occasionally tilting my hand to a better angle. It’s a strange feeling but not a bad one. When she finishes with one hand, I reach out with the other.

She stares at my skin, tilting her head sideways. “What happened here?”

My scars. I pull my hand away fast—too fast. I jostle her arm, causing the bottle of Tahitian Breeze to fly through the air, finally landing upside down on the ground with a sickening crack. My cheeks get hot. Another bit of bad luck. Just when I was making a friend. Just when I was feeling normal.

Faith hops off the table and grabs the bottle. It’s not broken, but a lot of the polish spilled out.

“I’m so sorry,” I say.

Faith twists the cap back on. “I didn’t expect you to jump away, that’s all.”

My face burns. “I’ll buy you a new one.”

She shrugs. “There are worse things in the world.”

Faith sits on the table again and reaches for my hand. When she sees the surprise on my face, she smiles.

“I’m pretty sure I have enough. Okay?”

I nod. This time she doesn’t ask about my scars. She paints my nails with quick, confident strokes.

Usually, I don’t talk about what happened with my hand. Maybe it’s my contrary nature, but the fact that she isn’t asking sure makes me feel like telling.

I clear my throat. “My hand is scarred because a dog bit me. In this park, actually.”

Faith’s eyes widen and she looks around, like the dog could show up any minute. “Where?”

I point with my chin at a cluster of maple trees on a grassy ridge. “Ma used to bring Ray and me here all the time and lay out a blanket. She stepped away for a minute, and a dog came over and chomped my hand. Walked right past my brother, of course, and picked me to bite. That’s the kind of luck I have.”

Ma used to take us here to look at the view. We’d have picnics with a big jar of lemonade and freezer waffles. Ray and I used to roll down that hill until we were dizzy. Afterward, we’d visit the band shell, which used to have concerts all summer long. These days it’s a little run-down and could use a coat or two of paint, but back then it was the most fabulous place my little-kid self could imagine.

Faith’s still staring at my hand, her forehead crinkled in worry. “It must have hurt a lot.”

“Sometimes they itch or feel tight. But when I was little, I used to wish— Never mind.” I stop myself from finishing the sentence because I’m afraid it sounds silly.

Faith looks at me sideways. “Did you wish it was a magic scar? Like one that could tell the future?”

I wince, nodding. It sounds babyish, hearing it out loud like that.

Faith frowns. “My mom says it would be a burden to know the future—that we wouldn’t like it if we had that power.”

She says the words casually, like she knows millions of things about her mom. She probably does—she probably even knows what her mom ate for breakfast today. The thought of it makes my head fill up with questions like floating balloons. I don’t know what Ma thinks about the future. I only know she wanted one without me in it.

“But for me, I’d want to know. Would you?” Faith’s voice is serious, almost solemn.

“I’d want to know,” I say. “I don’t like not knowing things.”

Faith nods once, like we decided something important. “Me too.”

It feels like a puzzle clicking into place. She shows me how to blow on my fingernails to dry them, and I do. We watch the boys play. Ray makes an easy shot and Tyler scowls. They’re on different teams.

Faith bumps my shoulder. “Which one do you like?”

I wrinkle my nose. “None of them.”

She rolls her eyes. “But what if you had to pick one?”

“I guess … Javier?” He’s the nicest of Ray’s friends. Plus, I like his freckles and superlong eyelashes even if I don’t like him.

Faith nods. “Those eyes, right?”

I smile and she grins back. Maybe this is easier than I thought.

“What about you?”

She sighs and shakes her head. “When I lived here before, I liked Jordan—but not anymore.”

“Grant was looking over at you earlier,” I say.

Faith’s eyes get big. “Really? Hmmm.”

When the sun gets low in the sky, it’s time for Ray and me to go meet Dad for dinner. I say bye to Faith, and she says “see you later” with a wave of her turquoise-painted fingernails that match mine exactly.

We’re not real friends—not yet. But at least it’s something like it.

CHAPTER

6

The quickest way to Oak Branch’s downtown is to take the wooden pedestrian bridge that runs right over Glass Lake, which is surrounded on three sides by mountains. There’s a chill in the air, so I pull on my favorite green sweatshirt. By the time we make our way across, the sun is l

ow in the orange-sherbet sky. Beyond the lake, my mountains oversee it all—the purpling clouds, the deep blue water, my brother, and me.

Our town is small, and it’s seen better days. Some shop windows are boarded and vacant, and there aren’t as many people walking around as there used to be. But I love it anyway—it has everything we need. We get our groceries at Quinn’s Market, which closes early on Fridays. They’ve already brought their baskets of produce and flowers indoors. Oak Branch Books is a yellow building with big windows that look out on the water. The shelves run all the way to the ceiling, and there’s a tree house inside that you can climb up into.

Dad’s hardware store sits on the corner. It’s called Logan & Son, which is what it’s been called since Grandpa Floyd built it forty years ago. Dad was a baby then, but Grandpa already knew that his son would take over the business someday. And I guess someday Ray will run the store, too.

Once, I asked him why he didn’t change it to Logan & Son & Daughter, and he just sighed. “Annie, this is how it’s been and how it always will be.”

Practical. Predictable. The answer of a man who eats oatmeal for breakfast every day.

There are three restaurants in town. One is called H. Diggity. It’s painted blue and has pennants hanging in the windows. They serve hot dogs with homemade relish, salty french fries, and fresh-squeezed lemonade. Lulu’s is a coffee shop in a white brick building with crisp black awnings. They make my favorite corn muffins and serve them with strawberry butter.

The third restaurant is called JoJo & The Earl’s and it’s my favorite. They serve Carolina barbecue seven days a week. There’s no place like it in the world. And that’s where we are meeting Dad for dinner, like we do every Friday.

JoJo & The Earl’s is a long, narrow building that is painted red and yellow. The awnings are striped red and yellow. Even the flowers in the planter boxes are red and yellow! Inside is more of the same: half the restaurant is red and half of it is yellow. On one side, all the tables, seats, curtains, and walls are red. And on the other, yellow.

When we step inside, Ray and I help ourselves to the root beer barrel candy that’s kept in a glass dish at the register and is free to anyone who wants a piece. The Earl is busy taking orders from a table of people we don’t recognize, probably out-of-towners. I love The Earl, who looks like Santa, except minus the white beard and plus a big old Southern accent.

JoJo comes out from the back, carrying a couple of her famous chess pies. Her silver hair is in an updo held with pretty red and yellow clips. When she sees us, she beams.

“Let me get these in the case, and then I’m going to hug you both up,” she says. JoJo’s hugs are round and soft, just like JoJo.

She peers at us both. “I do believe you two have grown since last Friday.”

“Now, darlin’,” The Earl says from across the restaurant. “Don’t fuss too much at those young folk, or you’ll scare them off.”

“Hush, you,” she says back, but she’s not cross. Her voice is sweeter than all the pies in the case. She twinkles her special smile at The Earl, and he grins right back.

The restaurant is small enough that we can hear The Earl explaining. “You can order from either side of the menu, no matter where you sit. Yes, it’s unusual to serve both Eastern and Western barbecue at the same restaurant. But people do unusual things when love is concerned.” He catches JoJo’s eye and gives her an exaggerated wink. She shakes her head and rolls her eyes a bit, but she’s smiling.

The Earl turns back to his table. “North Carolina barbecue is a serious business, some would even say contentious. The eastern part of the state likes vinegar barbecue sauce, and the western part of the state likes Lexington style, which is made with an absolutely delicious red sauce, from a recipe that’s been handed down from one generation to the next.”

“Now, don’t let him talk you out of the vinegar,” JoJo calls. “You should at least give it a try.”

When my dad was little, The Earl was a young man and the restaurant was called simply “The Earl’s.” Famous for Western-style barbecue and red slaw made from The Earl’s great-granny’s secret formula. The restaurant was long but narrow, as it is today—only two tables wide. But back then, everything was painted red—exactly like the sauce they were famous for.

But years later, after my dad was grown and The Earl was even older, something amazing happened. The Earl fell in love with JoJo McCoy, our JoJo. The only trouble was that JoJo was from the eastern part of the state, far from the mountains and way down near the water where they do everything different, including their barbecue. JoJo liked vinegar barbecue only and couldn’t abide red sauce. She said she couldn’t work in a Western-style barbecue restaurant, even though she was admittedly in love with The Earl.

The Earl had to find a way to solve the problem. He closed the restaurant for four whole months. He moved east and learned from the best pitmasters in the region. He learned to make the vinegar and pepper sauce, without the slightest smidge of tomatoes. When he was ready to propose to JoJo, he asked her family for their support. And before they gave it, he had to make a meal that was up to standards.

It goes without saying that he earned their blessing. When JoJo and The Earl moved back to Oak Branch, they decided they would serve both kinds of barbecue. Which meant the restaurant needed some changes. JoJo sewed gingham curtains for every window, and they painted half the restaurant yellow.

The other big change was JoJo adding pancakes to the menu. She said she couldn’t bear to be part of a restaurant that didn’t serve pancakes.

Ray and I plop down at our favorite table—a four-seater in the exact middle where the red half and the yellow half meet each other. The table is painted half and half, too. I sit on the yellow side, and Ray sits on red. Swinging my legs, I let the spicy-sweet root beer candy melt on my tongue as I look at the menu. After all, looking at the menu is a Friday night tradition—even though we both have it memorized.

JoJo brings over our drinks—lemonade for me, an unsweet tea for Dad, and an Arnold Palmer for Ray, which is a fancy way of saying half lemonade and half tea.

“Your dad coming along in a bit?” she asks.

Ray and I nod. Dad running late to dinner is nothing new. He would never rush a customer out of the store, even if it means working after closing time.

She places a fistful of root beer candy between us. “Don’t forget to save a little room for dessert,” she says.

Ray and I grin at each other. No matter how full we are, we can always make room for a slice or two of JoJo’s pie.

I’m on my second lemonade and my eighth root beer candy by the time Dad joins us.

The Earl ambles over to take our orders. He pushes his thick black glasses up on his nose and winks. “How’s my favorite Friday night family?”

Even though he says it to everyone, I think he means it extra for us.

After we finish ordering, The Earl tucks his pen behind his ear and looks at Dad. “You told them the news?”

Dad smiles. “Not yet.”

After The Earl walks away, Ray and I look at Dad. He sips his tea with an innocent look on his face.

“What news?” I ask. Ray’s too polite to be so direct, but politeness doesn’t get questions answered.

Dad puts down his glass. “You know Oak Branch is losing all its tourist trade to Mountain Ring. The town council is working on creating our own draw here in Oak Branch.”

I scrunch my forehead. “Mountain Ring is so fancy. How can Oak Branch compare?”

Ray frowns at me. “That sounds disloyal, Annie.”

He makes it sound like I should be tried for treason.

I glare back at him. “Don’t blame me. I love Oak Branch more than anyone. It’s not my fault that Mountain Ring is more popular.”

“We have a wonderful downtown, hiking trails to the Big Little Waterfall, and the best view of the Blue Ridge Mountains,” Dad says, sounding just like a brochure at our dilapidated visitors’ center. �

�But we’re small. As a town, we’ve been struggling. We’re hoping this festival will put Oak Branch on the map.”

“What festival?” Ray and I ask at the same time.

Dad’s eyes shine. “The Rosy Maple Moth Festival.”

He says it like he thinks we’ll burst into applause. But instead, Ray and I look at each other. Dad’s lost his mind.

“Sparksville has a Firefly Festival,” Dad continues. “And Elwindale has Ladybug Fest. We thought this could do the same thing for Oak Branch.”

Ray looks sideways at me. I grimace back.

“With moths?” I ask.

Dad frowns. “What’s wrong with moths?”

“Dad,” I say patiently. “People like fireflies and ladybugs. I’ve never met anyone who likes moths. Right, Ray?”

Dad looks perplexed. “Son, back me up. Moths are as important as any other creature.”

Ray grimaces. “Yeah, but a whole festival? I don’t know, Dad … they’re kind of ugly.”

Finding myself and Ray on the same side of an issue is so unusual, I’m stunned into silence.

“The rosy maple isn’t any moth,” Dad says. “You know which ones I’m talking about, right?”

Ray shakes his head. “Never heard of them.”

“Me neither,” I say.

Dad pulls his phone from his pocket. When the page loads, he holds it out to us. “Behold, the rosy maple!”

I’m afraid of what I’ll see but still lean forward for a closer look. Ray does the same. When we see it, we gasp.

The rosy maple moth is beautiful.

I know I’m not much of a bug person, but I thought I knew moths. Every moth I’ve ever seen was a muted grayish brown—the exact color of dust. But the rosy maple moth is something else entirely. I can’t stop staring at it.

The rosy maple moth is not the color of dust. It’s hot pink and bright yellow. It looks like it was crayoned with the brightest colors in the box. My fingers itch to draw it—I’m already planning how to match the bright hues of this funny, furry little creature.

These Unlucky Stars

These Unlucky Stars