- Home

- Gillian McDunn

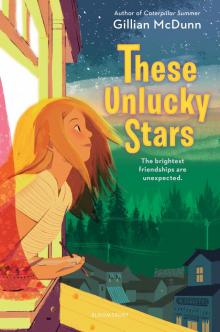

These Unlucky Stars Page 2

These Unlucky Stars Read online

Page 2

It’s a sandwich—Ray’s usual turkey, lettuce, and mustard on whole wheat.

I peer at it doubtfully. My brother is a lot of things, but never have I known him to be a random sandwich giver.

I frown. “What’s this for?”

He doesn’t take his eyes off the street. “I thought you might like to eat today.”

I go backward through my thoughts. Then, groaning, I smack myself on the forehead. He’s right. After everything this morning with Dad and the window, I never packed a lunch. There’s only one thing I can’t figure out.

“How did you know?”

The corner of his mouth quirks up. “Your entire backpack just emptied out into a mud puddle, remember? I didn’t see your bag.”

I hesitate. “Are you sure? Won’t you be hungry?”

Ray shrugs. “I have peanut butter crackers and raisins in my bag.”

“Raisins! Blech,” I tell him. Only Ray would pack raisins, of all things.

He doesn’t say a word.

“Thanks,” I say.

“Not a big deal,” Ray says. “Come on—let’s cross.”

We step into the street, and something catches my eye—something on the road. At first I think it’s a small rock. But then it moves. Sitting in the middle of the double-striped yellow lines is a tiny turtle.

I grab Ray’s arm. “Look!”

Ray glances at it and shrugs. “Probably looking for water this time of year.”

“Of all the roads to cross, this is the worst one possible,” I say. “That’s some bad luck right there.”

Ray ignores me. We reach the path, and for a moment I’m swept along in the masses of kids heading to school. They’re talking and swinging their backpacks. Ray starts to move more quickly, too—but I can’t stop thinking about that turtle in the road.

I pull his sleeve. “Do you think it made it across?”

Ray frowns. “What are you talking about?”

I give him a look. “The turtle. It needs our help. We have to go back.”

Ray lets out a big sigh, like he thinks I’m being ridiculous. “You don’t even like animals. Quit trying to make me late.”

“That’s completely unfair,” I say. “I do so like animals.”

“Oh really,” he says. “Since when?”

I cross my arms. “Since now.”

He shakes his head. “What about dogs?”

I hold up my scarred hand. “Remember this? I have a good reason not to like dogs.”

He squints at me. “Cats?”

“They make me itch,” I admit.

“Birds?”

I shudder. “Creepy things descended from dinosaurs? No thanks.”

“I’ve seen you flip out over bugs, so I’ll assume that’s a no,” he says. “Same for lizards and bats.”

“Other than that, though, I don’t mind them one bit,” I say.

He rolls his eyes. “For instance?”

I think fast. “Like deer. I see them in the woods sometimes, and they are real sweet with their babies. Or maybe, like, koalas? We saw that one at the zoo and it was really cute.”

Ray turns to go.

“Or fish, Ray! I don’t mind fish!” I yell at his back.

He doesn’t even pause for a second. I know I should follow him, but the turtle is all I can think of. I’m on a mission.

As I head back to the busy road, my heart beats in my throat. I don’t know what I’ll do if she’s been smashed by a car. I have decided the turtle is a she.

But when I get there, I breathe a sigh of relief. There she is, on the yellow lines like she’s decided it’s a grand place for a morning rest.

“That’s a dangerous spot to linger,” I tell her.

She blinks.

“Go on,” I say. “Get yourself out of the road.”

She doesn’t budge.

I need to do something.

Before I can lose my nerve, I dash into the street. I reach down and scoop her right up. This startles her, and she tucks herself into her shell.

“It’s okay,” I tell her. “You’re safe now.”

But even as I’m saying the words, I feel a rumbling. I turn my head. Bearing down on us is an enormous truck, going way too fast. There’s no time to move. I stand right there on the yellow stripes, squeeze the tiny turtle to my chest, and pray. It’s not a prayer with words; it’s more of a prayer with feeling—the feeling of: please no, please no, please no, please no—

The truck roars by with the blare of a horn.

“Get out of the road, kid!” a man yells out the window.

“Aw!” I yell back. “You get out of the road yourself!”

I glare at the retreating vehicle, already too far away to hear my reply

I check on the turtle, who I have decided to name Esmeralda. “We made it. Are you okay?”

Turtles don’t nod, but she blinks again, and I think she’s saying “Whew, that was a close one, but I’m fine.” I hold her carefully, and in four jumps we are safe on the sidewalk. My heart is roaring and my breath is unsteady. But when I look at the turtle, she peeks out at me, smiling. Well, not smiling exactly. I don’t know if turtles smile. But at least it’s something like it.

I can’t help grinning. “Well, aren’t you cool as a cucumber after staring death straight in the eye.”

She squints, which probably means “thank you” in her turtle language. It makes my heart fill up. We are understanding each other just fine.

I cradle her to my chest and walk farther on the trail to school.

Dad has a no-pets rule, but I wonder if I might keep her. She wouldn’t take up much space. Maybe I could teach her some turtle tricks. She’s already mastered squinting and blinking.

But Dad says no exceptions. Not even a hermit crab. Not even a goldfish. I could keep her on my roof. But that doesn’t seem like it would be a good life for a turtle.

I reach the front of the school, which serves all the kids in Oak Branch up until high school, when we’ll have to take the bus over to Mountain Ring. The courtyard is empty. I guess the final bell rang when I was saving Esmeralda. I head over to a patch of turf by the stream that meanders near the trail. Gently, I lower her to the grass.

“It’s up to you,” I whisper. “If you want to be wild, walk away. If you want to be with me, stay right where you are.”

She pauses for a long moment. Maybe today is my lucky day. Maybe she’ll be mine. But then she starts to stir. Before I know it—without even a blink—she crawls away.

As she disappears under a bush, my heart folds in on itself. Goodbye, Esmeralda. You were almost a friend.

I straighten, pulling my backpack onto my shoulder.

“Annie Logan,” says a deep voice behind me.

When I turn around, Mr. Melendez is peering at me. He’s the school principal, and right now his forehead is wrinkled like a walnut shell.

“Mr. Melendez,” I squeak.

“Annie Logan,” he says. “Why don’t you follow me to my office?”

He says it like a question, but it’s not the kind that wants an answer. It looks like my regular old bad luck just got a whole lot worse.

CHAPTER

4

I can’t believe I’m late to school. I can’t believe I got caught. The only thing I can believe? My terrible luck that got me here in the first place.

Mr. Melendez tells me he will be right back. He disappears down the hallway. Across from his desk are two orange plastic chairs. I lower myself into one. The seat is curved in a way that pinches my rear end on both sides. It is extremely uncomfortable.

I try to distract myself by looking at the art on Mr. Melendez’s walls. “Distracting” is a good word for it. Instead of the usual inspirational posters or student work, Mr. Melendez has an assortment of unusual paintings. One is so bright, it almost hurts my eyes—a painting done entirely in shades of yellow and orange of two children with sinister expressions holding a bucket, standing on a hill. It seems like what might happen if someone cr

ossed a nursery rhyme with a nightmare.

I shudder and keep looking around the room. Included on the walls are paintings of: a barn and a wheelbarrow of potatoes, a monkey-bear creature wearing a birthday hat, and, my personal favorite, a towering stack of pancakes next to a waterfall.

I am bursting with questions for Mr. Melendez—did he paint these? Did he buy them? Sure, some of them are terrible—but at least they’re interesting. I’ll give him credit for that. But when he returns, he’s not alone. With him is Ms. Palumbo, my social studies teacher. The only thing I dislike more than social studies is Ms. Palumbo. If I could, I’d slide underneath this pinchy orange chair and hide.

Mr. Melendez sits behind his desk, and Ms. Palumbo pulls up the other orange chair. She’s narrower than I am, so the sides don’t squeeze her, but she perches on the edge of the seat anyway. She wears her black hair really short and today is wearing bold, geometric earrings in cadmium yellow.

“Thank you for waiting,” says Mr. Melendez.

“It’s not like I had a choice,” I answer.

He raises his eyebrows sharply. Oops. I wasn’t trying to have a smart mouth. Sometimes I can’t draw the line between what I should say out loud and what I should keep to myself.

“Sir,” I add, trying to recover.

He nods. I have noticed that sometimes a few well-placed sirs or ma’ams can go a long way—at least that’s true here in Oak Branch.

Before answering, he straightens a stack of papers on his desk. “We wanted to take the opportunity to check in with you. Ms. Palumbo mentioned that your work is uneven.”

My eyebrows draw together. So I’m not in trouble for being late—which should make me feel relieved. But it sounds like I’m in trouble for something else—maybe something worse.

I shift in my seat. “Not all my work. I have an A in art.”

“Mmm,” says Mr. Melendez. He says it like art doesn’t count, which makes me fighting mad. He searches in his pile of papers. “Ah, yes, here it is. Your teachers report that you are withdrawn and have few friends. You sit alone at lunch. Does that describe you, Annie?”

My cheeks burn. I gulp, looking back and forth from Ms. Palumbo to Mr. Melendez. They’re looking at me like a bug in a jar. How embarrassing.

Ms. Palumbo leans forward even farther, which makes her earrings swing so hard that they might fly off her ears. “I’ve seen this kind of thing before. Sometimes kids struggle when they have an exceptionally high-achieving older sibling.”

Oh. This is about Ray—how he’s good at everything and I’m not. How I will never be a citizen of excellence.

“We wondered if you might need a stronger support system for next year,” she continues.

My insides are like an escalator, rising and falling at the same time. So I’m not here because I’m in trouble. I’m here because they think I have troubles.

“A couple of weeks ago, I called and chatted with your dad,” Ms. Palumbo continues.

I raise my eyebrows. Dad never mentioned that.

Ms. Palumbo nods some more. I think her earrings might be hypnotizing me. “He said he wasn’t concerned as long as your grades were okay. But in my experience, grades paint only part of the picture. You have wonderful thoughts, but your teachers want to see you participate more. And being socially isolated is yet another concern, especially with those teen years right around the corner.”

“I-I’m not isolated.” I trip over the words. “I like to eat in the art room so I can draw.”

Ms. Palumbo makes a tsk sound in her throat. “I saw how you struggled with the group project this semester. I know you blew up and walked out of class.”

Every muscle in my body tenses up. Group projects are the absolute worst, and I don’t know why anyone pretends differently. Any friendship that survives a group project should be considered a downright miracle.

“It’s not my fault they couldn’t appreciate my illustrated time line of ancient Greece,” I tell her hotly. “Do you have any idea how many outer columns are in the Parthenon?”

They stare at me blankly.

“Forty-six,” I say, answering my own question.

Ms. Palumbo arches her eyebrow at Mr. Melendez. This makes me even madder.

“Besides, I do have friends,” I say. “I hang out with Ray and his friends all the time.”

Ms. Palumbo whirls on me, eyes glowing in triumph. “Exactly! Ray’s friends. Annie, you deserve to have your own friends. Have you ever tried taking the initiative and starting a conversation? Try saying ‘hi’ to someone!”

I look out the window, barely holding on to my last shred of patience. The buildings block the view of the mountains, which makes me feel doubly alone. What I really want to say is, “Wow, great advice, Ms. Palumbo. Talking to another human being and saying hello? I never would have thought of that one.”

Ms. Palumbo starts patting my arm in concern. I squirm away from her as much as I can, but she doesn’t get the hint. Each time she pats me, her earrings sway again. “I read in your file that Mom’s not in the picture. Is that right?”

Inside, I get that floaty balloon feeling, like something is just out of reach. My eyebrows go into a line, one that says “back off.” But she’s waiting for me to answer—she wants me to confirm what she already knows.

“So?” I say from between clenched teeth.

Ms. Palumbo makes a clucking sound. “Sometimes growing up is tricky, especially without a mother figure.”

My frown deepens. A mother figure? I open my mouth and close it again. For the moment, I seem to have forgotten what words are or how to use them.

Mr. Melendez pushes a pink piece of paper across the desk. “We have a program that could match you with a mentor. Someone to show you the ropes of, of—”

“Of becoming a woman!” Ms. Palumbo finishes triumphantly.

My stomach promptly coils into a ball. Ick, ick, ick. Why do adults always want to talk about puberty? It’s so gross, and I can tell that any second now, someone is going to use the word “blossoming,” as in “blossoming into a young lady.” If that happens, I will definitely melt into the floor and die.

“I already have a mentor,” I say quickly. “A great one! She’s really good at …”

My thoughts spin wildly. “Mentoring! Yes. She’s a good mentor who likes to … mentor. Almost every day, we mentor together.”

They exchange a glance like they don’t believe me. I better step it up.

I take a breath. “We both like art. And we talk about all kinds of things. It’s really good for me. It’s really good for my, ah, development.”

Mr. Melendez riffles through the papers on his desk. “She’s not named as your emergency contact. Is this a relative? A neighbor?”

“Yes,” I say.

He looks at me blankly.

“Oh! She’s, um, an aunt. And a neighbor. Like a neighbor-aunt. More of a family friend, you could say.”

Ms. Palumbo narrows her eyes suspiciously. “What’s her name?”

My neck starts to sweat. “Her name?”

Mr. Melendez holds his pencil, ready to write down my answer.

“Her name, good question. Her name is—” I look at the wall with the orange-and-yellow paintings. The two kids on the hill, like a terrifying version of Jack and Jill.

“Listen,” says Ms. Palumbo smoothly. “In cases like these—”

“Jack—Jackie!” I say it loud enough that they both jump slightly in their chairs.

Mr. Melendez writes it down. “Jackie. And her last name?”

I glance at the farm painting on the wall with the wheelbarrow of potatoes. I gulp.

“Spuds?” It comes out in barely a whisper.

Mr. Melendez’s brow wrinkles. “Spuds? How do you spell that?”

I can’t believe I said Spuds. No one has the last name of Spuds. If they find out I made up Jackie, they’ll definitely call Dad. I need to make it seem more real.

“I think with a Z?”

M

r. Melendez taps his pencil. “A Z?”

He says it like Zs can’t be trusted.

I need to commit. Need to really sell it.

“Two Zs,” I say firmly.

Mr. Melendez’s forehead grows a few extra wrinkles.

Ms. Palumbo looks like she’s ready to do a puberty intervention, right here in the principal’s office.

There’s no use in doing something halfway. If we surveyed turtles in the road, I’m positive that nine out of ten would agree.

I clear my throat. “I’ll spell it for you. Z … P … U …”

I’m off to a good start. Mr. Melendez scribbles to keep up.

“… D …”

Ms. Palumbo sniffs. My throat is suddenly dry.

“… Z,” I say.

Mr. Melendez blinks. He’s holding his pencil like he thinks I’m not done.

“And then one more Z,” I say, hoping that I sound more confident than I feel. “That’s it.”

He holds the paper in the air. “Z-P-U-D-Z-Z. Highly unusual.”

Ms. Palumbo frowns. “So it’s three Zs. Earlier you said two.”

I gulp. “Yes, three Zs. But they aren’t all together.”

She taps the desk. “And how did you say it’s pronounced?”

“Zpudzz,” my voice squeaks. “It’s Dutch-Romanian, on my mother’s side.”

“Ah,” says Ms. Palumbo.

“Dutch-Romanian,” says Mr. Melendez excitedly, like it suddenly makes sense. “Well, of course.”

“Of course,” I answer. “Indeed.”

Before they can answer, I launch myself out of the chair, slinging my backpack over my shoulder. “So, um. That’s great. Thanks for checking on me and all. And you know, I better get to class. Thanks again. Have a great summer. Ma’am. Sir.”

As I head for the door, I hold my breath. I’m sure they’ll call me back, but they don’t.

I close the door behind me. What a morning. First Esmeralda and now Jackie Zpudzz. The day has got to get better from here.

CHAPTER

5

The entire day passes in a blur. Even though school got out an hour ago, the words from Mr. Melendez and Ms. Palumbo spin through my mind like they’re on a carousel.

I’m at Oak Branch Community Park, sitting at the picnic table by the basketball courts. I should be happy. The sun is warm against my back and my mountains are crisp against the sky. My book is wide open, and I’ve sketched the beginnings of a few of the players. I’m not always good at capturing the feeling of movement, but usually I’m happy to try.

These Unlucky Stars

These Unlucky Stars