- Home

- Gillian McDunn

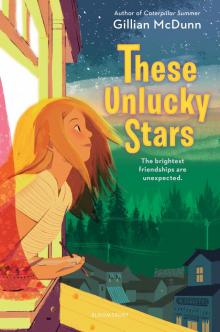

These Unlucky Stars

These Unlucky Stars Read online

For Leo

Also by Gillian McDunn

Caterpillar Summer

The Queen Bee and Me

CONTENTS

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Part Two

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Part Three

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Part Four

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Part Five

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Acknowledgments

PART ONE

Oatmeal: Portrait of a Family in Four Bowls

From the Collected Drawings of Annie P. Logan

CHAPTER

1

You can measure how lucky someone is by asking them whether they believe in it.

Lucky people say, “There’s no such thing.”

To them, the universe is orderly and kind. Hard work always leads to happiness. Life goes according to plan. They never notice the million times their luck steps in to save the day.

My brother, Ray, is like this. He’s a sunny-side-up, lemons-into-lemonade, golden-ticket kind of person. A real umbrella-remembering type.

I can hardly stand it.

The truth is, sometimes people try hard, but things don’t go their way. Ma used to see that about me. I may mess up, but I’m always trying.

Unlucky Annie, she’d whisper, gathering the pieces of the green glass lamp.

Of course, she’d murmur, dabbing at my bloody knees with a cool washcloth.

Born under an unlucky star, she’d say, like it was a song we both knew by heart.

Then she went away, when Ray was five and I was only four. Kissed us both goodbye and coasted her pumpkin-colored station wagon out of our long and narrow driveway—gone in the blink of a turn signal. We haven’t heard from her since.

Dad and Ray don’t talk about Ma. They don’t know I think about her all the time. I might be the only one who remembers the genius of spaghetti dinners eaten in the bathtub. I’m the only one who knows about those midnight thunderstorms where she and I huddled together on the plaid sofa, eating sliced plums. Who else would buy a preschooler squishy tubes of paint from the grown-up art store because some things are worth it?

She smelled like carrots fresh from the garden. Her hair was the exact color of a new penny.

I don’t know if it’s possible to wear out memories. She left before I had a chance to store up very many. My mind runs over the same ones again and again until they’ve almost gone smooth—like pebbles in the stream that winds behind our little house. At times I feel like I’m at the edge of remembering something more, something new—but it’s always just out of reach, floating away like a balloon with a too-short string.

If she were here, I’d want to know everything—all the good things and bad things. I’d ask her if she ever felt unlucky, too. I already know she believes in luck. But I wonder if she thinks a person can be so unlucky, they act as a magnet for trouble—a lightning rod that draws every bad thing directly their way.

In other words: Am I the reason she left?

But I have no one to ask, so for now I keep that question in a quiet corner of my heart.

CHAPTER

2

It’s probably true that given my track record for broken bones, broken things, and all-around bad luck in general, I have no business at all sitting on a roof.

But this roof is a good one.

It runs right outside my bedroom window and has the best view in all of Oak Branch, North Carolina. This is the spot where thick pine trees give way to a wide panorama of the Blue Ridge Mountains—also known as my mountains, because there’s no one in the world who loves them like I do.

Each morning, the roof practically calls my name. “Annie, come take a look. Your mountains are shining real pretty today.”

It’s an extremely persuasive roof.

However, Dad is not easily swayed. “Come down,” he’d argue. “You’ll break your head.”

But just like he needs coffee and oatmeal, I need my mountains and colored pencils to start the day. What Dad doesn’t know won’t hurt him.

I arrange my sketch pad on my knees and get to work making the lines of my mountains. Even though I have the peaks memorized, I’m never bored. Each time I see them, they show me something new. On hazy mornings like today, my mountains shimmer prettier than any old ocean. Evenings offer rainbow-swirl sunsets. And after bedtime, the sky turns to dark velvet with stars so bright, they look positively grabbable.

I lean against the wall, my back to Ray’s bedroom window. Never in a million years would my brother join me out here. He’s ten months older than I am and likes to point out that he’s also ten months wiser. But the truth is that he has a real stubborn rule-following streak. He cares more about being the best at everything than he does about appreciating the simple fact that he’s a hop, skip, and a jump from something downright glorious.

So this roof remains my own personal slice of heaven. Which is exactly how I like it.

“Annie! You’ll be late!”

Dad’s shout echoes up the stairs, bounces across my bedroom, and ricochets through my open window, finally landing square on me. I gulp, looking down at my drawing. I’ve been so deep in my thoughts that I’ve completely forgotten about that little thing called “school.”

“In a minute!” I yell back. But instead of scrambling to pick up my pencils, I turn to my paper once more. Using my index finger, I smudge crisp lines to softness until the mountains on the page feel as full and alive as the ones in front of me.

Now I need to hurry. I gather my pencils and zip them into their pouch. The morning light catches the bumps and lines on the back of my hand—a constellation of scars, also known as the souvenirs from a dog bite when I was little. Even though they’ve mostly faded into things that can be felt more than seen, I always know they’re there. And I still don’t trust dogs. Not one bit.

“Annie!” Dad yells again in a “right now and I mean it” voice.

Yikes. He’s louder now, his feet thudding on the staircase. I jump into action. Through the open window, I toss my pencil pouch and sketchbook onto my bed. The doorknob jiggles just as I aim one foot through the window. I freeze.

The door swings open, and Dad’s shoulders fill the frame. His eyes widen as he takes in the scene. One innocent left foot planted on the scuffed wood floor. One guilty right foot out on the roof. That’s me: half good intentions and half bad luck.

Dad pauses and I wait like that, wondering what will happen next. Today, like every morning, his dark hair

is combed and his face is freshly shaved. Dad has no patience for the magic of crawling on roofs. He doesn’t understand morning drawings or the way mountains call to me. In fact, he doesn’t understand me at all. It’s not his fault—he’s practical. Predictable. If he were a food, he’d be oatmeal. If he were a color, he’d be beige.

The tips of his ears turn scarlet. My eyebrows pop up. I’ve never seen him lose his temper. It’s not like I want him to yell at me—but if he did, I wouldn’t mind it. At least then I’d know what he was feeling.

But the explosion doesn’t come. Instead, he seems to swallow his fury. Instead of yelling, he lets out a sigh. “Annie, you know you can’t be out there. Safety rules.”

I try to think fast. “Dad, can we relax a few of those rules? I need this view like I need oxygen. It’s not my fault that all these trees have grown up so big that I can’t see my mountains from my window anymore—”

Dad shakes his head, cutting me off. “Not a chance. You’ll break your head!”

Anger stirs in my chest. Just like always. Dad thinks I’m careless, a baby who needs to be protected—but he’s wrong. I’m eleven years old, and I’m a lot more responsible than he gives me credit for. I may not be perfect but he doesn’t see how hard I try.

I cross my arms. “I’ve been out on the roof every day this year and haven’t come anywhere close to falling off. Not even once!”

When I realize what I’ve done, I clap my hands over my mouth. I can’t believe I admitted to breaking his safety rules. My mind spins, trying to think of a way out.

“I mean—” I start.

A muscle in his jaw twitches.

“Later,” he says. His eyebrows are still pushed together in a line. “Time for school. Your brother is waiting.”

It’s his “no use arguing” voice, which is so unfair. I bring my foot inside with a stomp and then shut the window with a bang.

I’m so mad that I barely notice the tinkling sound the glass makes. But no matter how mad I am, there’s no mistaking what I did to my window. A crack splits sideways across it like a river searching for shore.

I wince. Late for school and a broken window? It looks like this is one of those days where my bad luck goes overboard.

In slow motion, Dad takes in a giant breath. It lasts so long, I think his lungs might pop. But then he lets it out in a whoosh.

“You can’t get carried away like this,” Dad says. “You’re so careless sometimes.”

Not careless. Unlucky. First that he caught me, then that the window broke.

I open my mouth, but he holds up his hand to stop me.

“I’ll tape it up. Go on to school or you’ll be late.”

He rubs at his temples like he has a headache. I grab my backpack and head downstairs, taking the steps two at a time.

Ray waits by the front door. “You’re late. Again. If you mess up my year, I will never forgive you.”

I sigh. My brother is an excellent citizen. And by excellent citizen, I mean Excellent Citizen. Capitalized, like it is on the trophy he’s won the last four years. Part of that award is perfect attendance with no tardies. Just my luck to end up with a brother who’s the absolute opposite of me.

I scowl. “Not everyone is a human alarm clock.”

But he’s already stepped outside, leaving me talking to the door. I grab my sweatshirt and follow after him. He’s practically halfway down the driveway already.

I shake my head. Walking to school is Dad’s grand plan to establish our self-reliance and grit. I can’t say that it’s working. But I don’t mind it on a day like today, when I get a little extra time to breathe in the pine-scented mountain air.

I catch up to him at the base of the driveway. “Hey.”

He doesn’t answer.

“You can’t be mad on such a gorgeous day. Don’t you love the morning air?” I breathe in deep.

“Did you get in trouble for being on the roof again?” he asks.

I frown. “Not really. He was angry, but you know Dad. He never says much.”

“Figures,” he says flatly.

“You mean it figures I’d be unlucky enough to get caught,” I tell him.

He shrugs. “More like stubborn as a rock. You know you aren’t supposed to be out there.”

I kick at a stone on the path. “I’m not stubborn. I’m unlucky.”

Ray tilts his head at me. “Luck is just a way people explain bad choices.”

That is such an annoying thing to say. My being on the roof with my mountains is not a bad choice. It’s necessary. Essential. But I shouldn’t be surprised that my brother doesn’t understand me. He never has and never will.

“You wouldn’t believe in a lucky star if one smacked you upside the head!” The words come out louder than I was expecting. I think Ray is going to get mad, but instead his forehead is lined in a thoughtful scrunch. He’s quiet, almost like he’s thinking it over. He’s really listening to me this time.

“That’s not true,” he says slowly. I feel my hopes rise.

“Really?” I ask. My heart starts to beat faster. Finally, we’re going to be able to talk about something important to me—something real.

Ray taps his chin. “If one of your stars smacked into me, I’d believe something all right.”

I bite my lip. “You would?”

Ray grins. “I’d believe that I needed to get my head examined.”

My hopes deflate like a three-day-old balloon. Ray and I will never see eye-to-eye.

He’s got a million friends and I can barely get one to stick.

He can do any sport he tries, and I’m a walking disaster.

We even look different. Ray’s hair is dark and wavy—like Dad’s—while mine is light brown and straight like Ma’s. He’s tall and lean and I’m short and round. His skin is smooth and even, while mine is sprinkled with freckles like someone threw handfuls of confetti. And don’t even get me started on the fact that he didn’t need braces and has never had a pimple.

He and Dad are exactly the same. Which makes me think I must take after Ma.

If she had stayed, life would be easier. Right now, Dad, Ray, and I form a skinny, lopsided triangle. They’re all the way over on one side, and I’m on the other. If Ma were here, she would help balance it out. I’m not saying our family was ever destined to form a perfect square. But at this point, I’d take a trapezoid.

We head to the narrow trail that shortcuts to school. The path threads between houses and requires hopping over a couple of low fences, but no one minds. The only drawback is that this time of year, there can be a whole lot of—

My foot slips, and I skid into a murky muddle the color of milk chocolate.

“Ugh!” I say, looking down at my new checkerboard Vans, which are soaking through quickly.

Ray’s on the other side of the puddle. “Why didn’t you jump over it like I did?”

I can’t stand the pain of admitting I wasn’t paying attention. I throw him a sour look and don’t reply.

Gingerly, I move toward the edge of the lake of mud. Please don’t let me land on my rear end. Finally, I make it to solid ground. The first thing I do is look at my shoes. They’re probably stained forever, but later I’ll throw them in the wash. For now, all I can do is try to wipe off the big blobs. I fish a tissue out of my pocket and lean over to work on my right toe—but as I do, I feel a minor avalanche cascading over my shoulders and head. The entire contents of my backpack—my folders, my library book, my homework for Ms. Palumbo, even my favorite pencil pouch—are now soaking in the mud.

Groaning, I clap my hands over my eyes. I can’t bear to look.

“Well, don’t just stand there!” Ray doesn’t hide the irritation in his voice. I peek between my fingers and see him collecting everything piece by piece.

He holds up a dripping sheet of paper. “Your homework is a goner.”

The ink has run onto the pages and is unreadable. The library book jacket will wipe clean, but the pages are dotted w

ith streaks and splashes of mud. The pencil pouch is disgusting, but I might be able to clean the pencils themselves. What a mess. I shove everything in my backpack.

“Make sure you zip it this time,” Ray says.

“It was zipped—it came undone on its own!” Or maybe I was in such a hurry, I forgot. But I won’t admit it, not even for a million dollars.

He rolls his eyes. “Yeah, sure. A zipped backpack magically opened when you leaned over. And that mud was out to get you, the way it jumped up and hit you in a tidal wave out of nowhere. It had nothing to do with the fact that you weren’t watching where you were going.”

He turns and starts walking away.

I hurry to catch up. “This is what I’m telling you! It’s my bad luck. This kind of thing would never happen to you.”

Ray kicks at the path, scattering tiny pebbles in front of us. “I’m not any luckier than you. The difference is that I don’t blame the stars when bad things happen.”

“How many library books have you ever dropped in the mud?” I ask.

He doesn’t answer. Instead, he puts on a burst of speed and I’m hurrying again, my muddy shoes squishing with every step. I’m not perfect like Ray, and I never will be. My life would be easier if everyone understood that.

CHAPTER

3

He walks ahead of me. I don’t bother hustling to catch up, because I know he’ll have to wait to cross at Ledge Road—it’s busy with cars, like it is every morning.

Most of the traffic heads in the direction of Mountain Ring. Almost none travels toward Oak Branch. Dad says that Mountain Ring is booming—it’s being built up fast with expensive shops, fancy restaurants, and rows of houses on their mountainside. Two years ago, they opened their own schools and took all the Mountain Ring kids out of Oak Branch. Meanwhile, our little town struggles to keep its shops and schools going. It doesn’t seem fair.

I was right—when I get to Ledge Road, Ray is standing there waiting for a gap in traffic. I come up next to him and am about to make a comment about how he shouldn’t rush ahead just to spend time standing still. But before I can say anything, he reaches over and shoves a baggie into my hand.

These Unlucky Stars

These Unlucky Stars